sswan

Sustainable Solutions for Water and Nature

The water network and the environment are at breaking point and change is needed. We must seize the opportunity to align economic and environmental regulation and make the biggest structural reform of our water system in a generation.

Facing the challenge head on we can be ambitious and innovative and drive impactful and meaningful change. We need to be brave and to invest in our future: both for the health of our waterways, the natural environment and for society.

The new SSWAN model shifts regulation towards catchment-based approaches to support cheaper, more innovative, more collaborative projects that more accurately reflect local priorities.

For more, read the SSWAN Discussion Paper.

A new approach

SSWAN seeks to restore and protect nature and to find sustainable solutions to ensure our waterbodies continue to sustain the health and wellbeing of people, as well as the natural habitats we all value and enjoy.

SSWAN advocates a catchment-based, holistic approach to managing our water courses, putting the emphasis on nature-based and low carbon solutions to benefit water, nature and society as a whole.

It sets out a vision for a new regulatory approach: one that focuses on the management of water catchments, drives environmental improvement at a national level, takes account of local preferences, circumstances and objectives, and enables all organisations affecting and managing catchments to innovate and accelerate environmental improvement in a cost-effective way.

The foundation of this new, more joined-up regulatory model is stronger accountability, with national targets tailored to local circumstances.

For more information read the SSWAN Discussion Paper.

A blueprint for reform

Our regulatory system could be more flexible, with more of a focus on what companies achieve rather than what they do.

We need more focus on nature and our customers, and we need the necessary resources and incentives in place to encourage collaboration.

A more cost-effective, outcomes-based approach will help build trust and restore nature, with regulation focusing on the end results: Is the water quality improving? Is there more biodiversity? Is nature thriving?

The key to this is local tailored delivery at catchment and sub catchment level - involving actors from all sectors contributing to address water health.

SSWAN proposes a four-tier regulatory framework:

Government: sets national policies and targets.

Regulators: accountable for ensuring the delivery of the outcomes set by government. They would regulate outcomes in individual water catchments, with localised targets tailored to individual catchments and reflecting local needs.

Catchment Advisory Boards (CABs): ensure the local objectives reflect local priorities, empowering local government and communities to provide tailored guidance to the regulators.

Joint Area Teams (JAT): determine catchment-specific short and long-term outcomes, setting targets and defining the monitoring requirements for each catchment.

This new model will enable a fundamentally different way of working and has the potential to unlock innovation and improve partnership collaboration. The potential benefits are substantial.

For more information read the SSWAN Discussion Paper.

Call to action

We face water, climate, and nature emergencies. We need the biggest structural shift in generations to rethink how we finance, regulate, and reform our water system to deliver better societal outcomes.

A new parliament should initiate regulatory reform to:

- Set river health targets at a national and catchment scale, ensuring the policy levers and incentives are in place to reduce pollutants and deliver targets locally.

- Link investment and targets across water quality, nature recovery, carbon, and climate to create new sources of funding.

- Ensure pollution is accurately apportioned to those responsible with detailed and transparent monitoring carried out by public bodies.

- Establish independent Catchment Advisory Boards to facilitate local decision making and deliver targets efficiently.

- Resource the regulators to drive compliance and sufficient investment in the water system, using existing enforcement tools.

- Set a framework to deliver long-term resilience, established by an independent body, and requiring water companies and regulators to deliver against the framework.

sswan in action

We have created two theoretical catchments – one urban and one rural.

Urban catchment management

On the left bank the illustrations show what the catchment would look like if we continue with business as usual. The right hand side of the river shows how things could be if we take a more holistic, catchment-wide approach, working in partnership.

Housing on floodplain

Building on floodplains means that the water has nowhere to go when the rivers or coastal waters flood.

River or sea water can no longer spread across the built-up land, which puts pressure elsewhere in the catchment, causing greater flood risk.

Factory and car park

Certain hard surfaces we use to build infrastructure create impermeable surfaces. This means rainwater can’t drain back into the ground, which creates more surface water runoff and can lead to problems, including localised flooding.

To reduce the risk of flooding, surface water is often connected into combined sewerage systems which reduces the sewer systems capacity and leads to the operation of storm overflows. Surface water run-off can also transfer chemicals, animal waste and other road pollution into rivers.

Supermarket and car park

Hard paving – no sustainable drainage.

Sports centre and car park

Impermeable ground and poor drainage.

School

Hard paving – no sustainable drainage.

Home and tower block

Hard paving and poor drainage

Hard paving and poor drainage. Appropriately sized drainage systems maintained by local authorities, can improve this situation. The use of sustainable drainage systems (SuDs), such as soakaways, can improve drainage, capturing some pollutants and enhancing the look and feel of an area and provide habitats for wildlife.

Rubbish in rivers

Rubbish is pollution.

Throwing rubbish into the river has an impact on the water quality and can be dangerous for wildlife.

Built up river bank and no or inadequate drainage

This can lead to localised flooding and standing water on roads and pavements, which can be dangerous and inconvenient. Lack of capacity in road drains, whether due to size or lack of maintenance, can cause flooding. Runoff from highways can transfer pollutants from vehicles, (oil, chemicals, particles from tyres and brakes) directly into rivers.

Improving the size and maintenance of drainage can help, along with sustainable drainage systems such as soakaways, which also enhance the look and feel of the area and provide wildlife habitats.

Dog mess

Cleaning up after your dog prevents dog waste getting into the drains and polluting rivers.

Sports drainage

Impermeable ground and poor drainage. Certain materials like those used to build some sports pitches make the ground impermeable. This acts as a barrier to water draining back into the ground.

SSWAN approach

SuDs – sustainable drainage systems are designed to manage stormwater locally, to mimic natural drainage.

Swale – a shallow drainage channel where rainwater run-off from roads or car parks can collect and soak away.

Flood plain allowed to do its thing

Natural drainage, prevents flooding downstream/into homes. Understanding the natural character of watercourses and preserving a natural floodplain allows space for water and reduces the risk to communities and buildings. By adopting Natural Flood Management and re-naturalising watercourses the environment can act as a store and sponge for flood waters, while also boosting biodiversity.

WRC and outflow into river/sea

Water recycling centres treat the foul and storm water from the sewerage system so that it can be returned to the environment.

The Environment Agency (EA) sets conditions which specify the level of treatment required to ensure that the treated water does not have an environmental impact.

The EA works with water companies to identify sites needing improvement and companies seek approval from Ofwat to expand or improve treatment systems. Nature-based solutions such as reed beds are an additional solution for treating final effluent.

Supermarkets with SUDS

Separation at source is good rainwater management and supports biodiversity. Reeds, grassed banks and nearby trees can be planted to create SuDs, improving biodiversity and aiding water drainage. These features can also enhance access to nature and provide wellness opportunities for local communities.

Town hall with SuDs and water gardens

Separation at source is good rainwater management and supports biodiversity. Rainwater separated before entering the sewer system and piped to a soakaway, pond or swale to facilitate the water to drain through grass and ground surface into the groundwater below helps recharge the underlying aquafer.

SuDs also slow rainwater runoff into rivers and combined sewer system to reduce flooding and storm overflow operation. SuDs also provide filtrations to help remove suspended solids and particulate contaminants from entering groundwater.

Rainwater gardens can create an improved environment, enhancing access to nature and providing wellness space for local communities.

Biodiversity

Creating and nurturing places for native plants to flourish encourages biodiversity and brings nature into our towns and cities. This is good for wildlife and wellbeing.

School with water garden

Including sustainable drainage and water gardens in playgrounds and schools can reduce surface water runoff, allow rainwater to drain naturally through the soil and improve the environment by boosting wildlife.

Grass sports pitch

A grass or permeable ground enables good rainwater management.

Grassed playground

Including sustainable drainage and permeable natural surfaces in playgrounds and schools can reduce surface water runoff, allow rainwater to drain naturally through the soil into groundwater aquifers while also improving the environment by boosting wildlife.

Soakaway

Separation at source is good rainwater management and encourages biodiversity. Soakaways can come in different shapes and sizes, from linear swales to grass plots. Rainwater from buildings and hard surfaces is piped to a soakaway to allow the water to drain through the grass and ground surface into the groundwater below to help refill the underlying aquifer.

They also provide some filtration to help remove tiny polluting and chemical particles from entering the groundwater.

Park with pond/SuDs

Separation at source is good rainwater management. Ponds and SuDs slow rainwater runoff into rivers and combined sewer systems to reduce flooding and storm overflow operation. Porous paving enables rainwater to drain into the ground, soakaways, rain gardens or water butts.

Soakaways and rain gardens can improve local areas, encourage more wildlife, improve urban cooling and offer greater environmental resilience.

House with garden

Natural drainage. Gardens provide an excellent place for wildlife and an opportunity to improve the local environment. Gardens with grass, trees, hedges and flowerbeds use rainwater and the excess can drain naturally through the soil into the groundwater aquifers.

Water butt

Saving water and separation at source is good rainwater management. Water butts are a great way to capture rainwater falling on roofs. They provide two functions:

- to provide an alternative to tap water when watering the garden and thereby saving water and

- to accommodate rainwater and separate it at source rather than it flowing directly into a combined sewer and increasing storm overflow discharges.

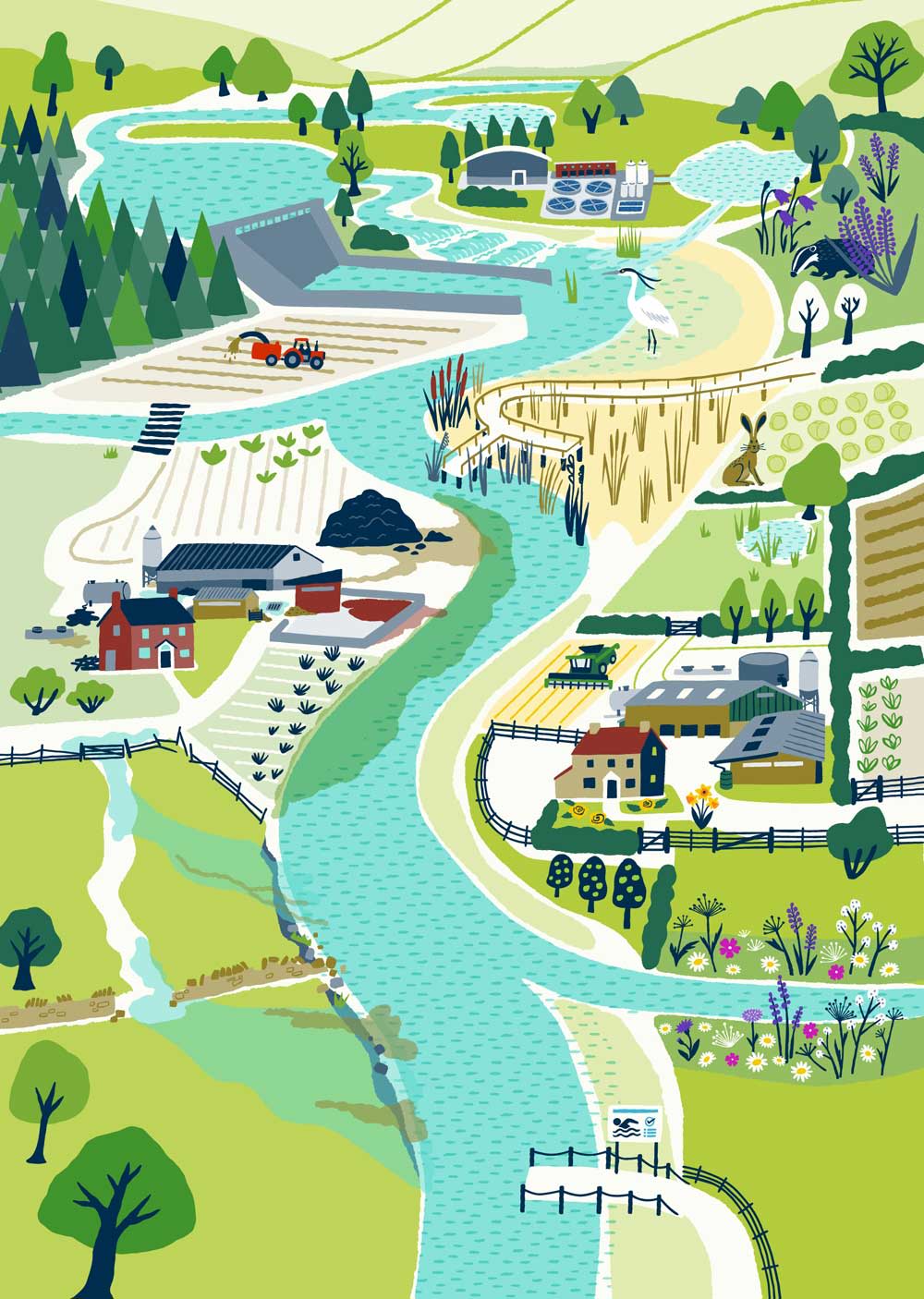

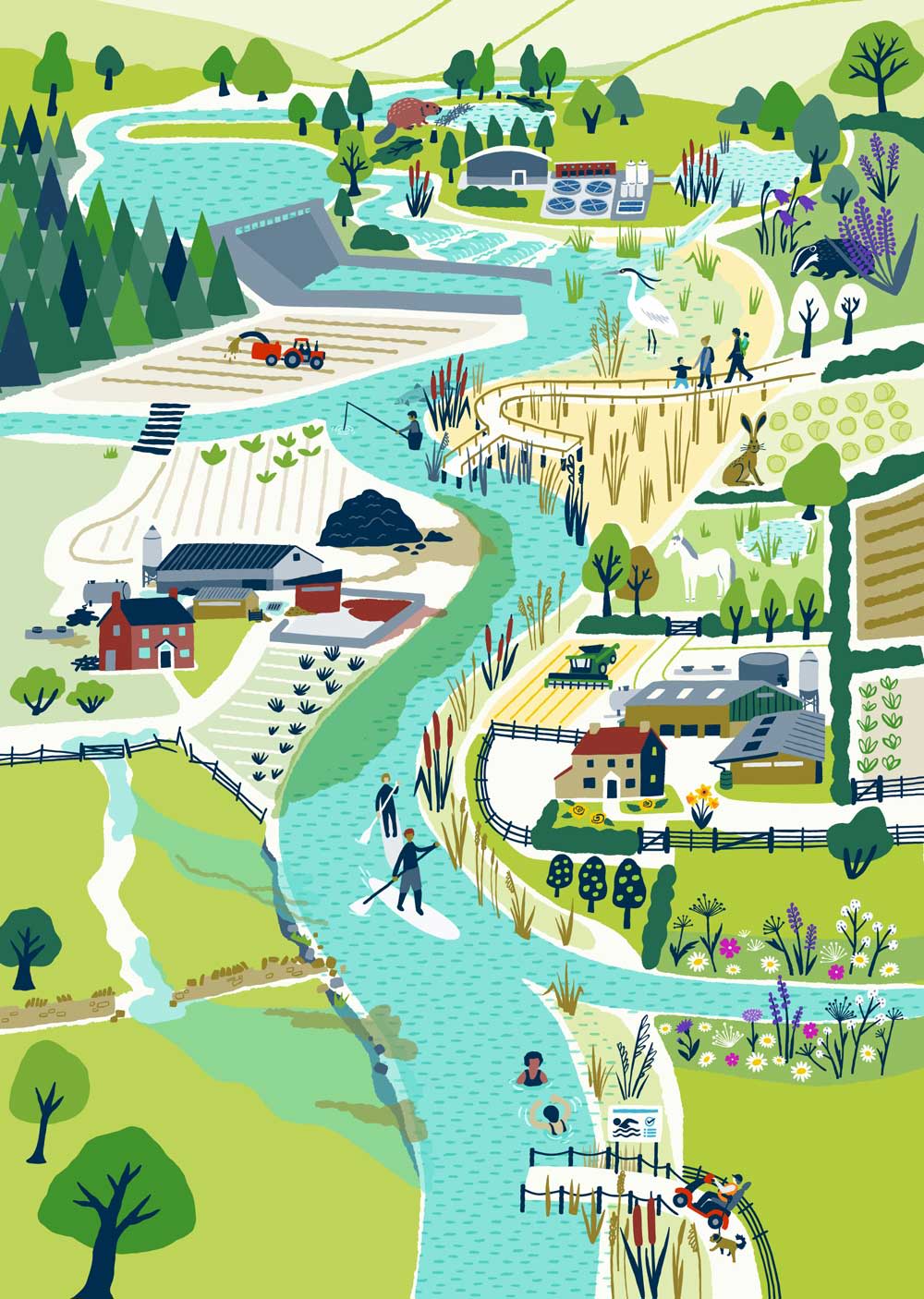

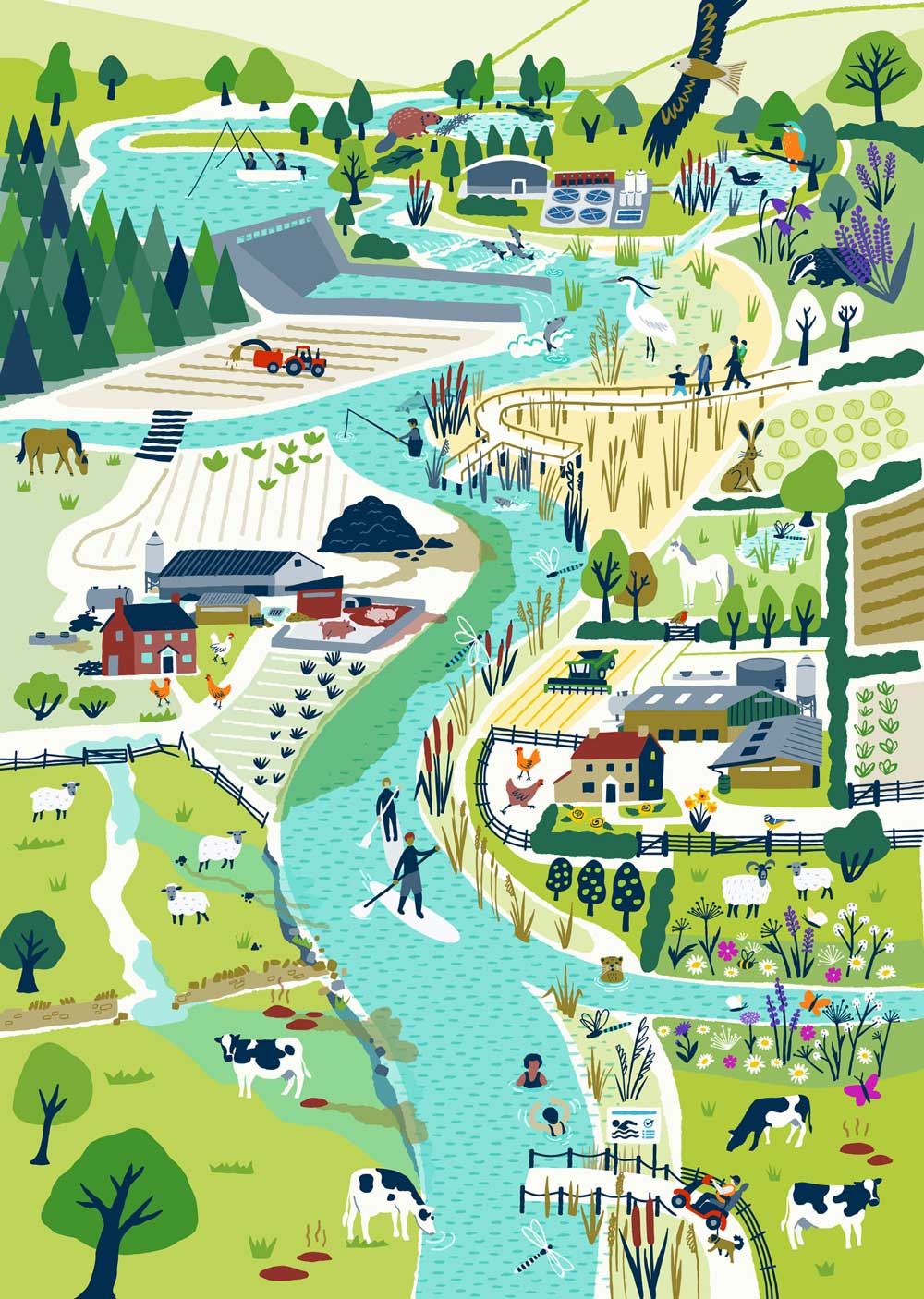

Rural catchment management

On the left bank the illustrations show what the catchment would look like if we continue with business as usual.

The right hand side of the river shows how things could be if we take a more holistic, catchment-wide approach, working in partnership.

Barrier in river

Barriers such as dams and weirs can impede fish and eel movements, which has an impact on their spawning and leads to their decline which harms the wider river eco-systems. Barriers may have been installed to address flooding issues, or as part historical water level management or irrigation systems and may now be redundant. Many river groups have identified removal of these structures.

Fish or eel passes – bypass channels or grassy slopes – enable easier movement upstream to spawning grounds.

Trees planted to farm/harvest

Non-native species can damage biodiversity. Harvesting means damage to habitats and ability for life to flourish. While plantations are important for forestry and wood production, non-native plantations and monocultures can impact the wider diversity of wildlife within the countryside. A lack of diversity means lower environmental resilience and susceptibility to disease or climatic pressure, as well as contributing to decline in certain species.

Slurry

Manures and slurries from farm animals can be a sustainable way of providing nutrients to crops. However, excessive use of slurry, or applying it during the wrong weather conditions such as heavy rainfall, can cause increased levels of nutrients to be washed off the land into rivers, contributing to eutrophication and damaging habitats.

Poorly maintained agricultural sites

Poor management of fuels and agricultural chemicals can lead to soil and water contamination. While this is rare, it can still happen and can harm both groundwater and river water, and also affect water supply sources such as boreholes or reservoirs. Fuels and chemicals should be appropriately used, securely captured and stored away from surface water drainage or water courses.

Road with poor drainage

Without good drainage infrastructure, roads act as pathways for runoff straight into the water environment. Road drains can contain contaminants including rubber, oil, metal, microplastics and anti-freeze from vehicles, and soil and litter from rural and urban runoff.

Crops right up to river’s edge

Grazing and cropping right up to the riverbank can increase the risk of run-off from these fields creating pollution in the river. Surface water running across fields can transport sediment, excess nutrients (from manure or fertilisers) and pathogens (from animals) into river channels. This can cause eutrophication, affect water quality and sediments can smother river habitats causing harm to fish and species living in the river.

Livestock in river

Although it is illegal to allow livestock to enter a river, it does sometimes happen. If farm animals enter rivers it can cause environmental problems from bankside erosion leading to sediment pollution in rivers, to the introduction of pathogens and nutrient contamination that compromise water quality for people and wildlife.

It can also harm the animals themselves as they may come in contact with pathogens in the watercourse, or slip and harm themselves.

Eroding riverbank allowing run off

There are many reasons why riverbanks erode: some are natural due to normal river processes, but this can be exacerbated by poor field, bankside and upper catchment management.

Riverbank erosion loses soil essential for growing crops and releases sediment into rivers which can transport pollutants such as nutrients or pathogens. It can also increase flooding downstream.

Where natural river forms are replaced by concrete or clay-lined channels the flow can increase, leading to greater erosion, undermining riverbanks and causing them to collapse, and creating higher levels of sediment pollution which affects fish habitats and water quality.

SSWAN approach

Now we'll go through examples of preferred rural management and what good it can do to the environment.

Reservoir

Sustainable abstraction: reservoirs are a vital source of drinking water and an important habitat for nature. They host recreational activities including fishing and walking and are highly valued by local communities. Water quality in reservoirs is influenced by surrounding land uses and the rivers that feed into them.

Reverting agricultural land to woodland, wetland or creating natural flood management can both improve water quality by filtering the water, create new wildlife-rich habitat and retain water for longer, reducing peaks and troughs associated with climate change.

Reedbeds by treatment works

Storm overflow management to minimise pollution: water recycling centres treat foul and stormwater from the sewerage system so it can be safely returned to the environment. The Environment Agency sets permits conditions which specify the level of treatment required to ensure there is no environmental impact.

Many settlements have traditional combined drainage systems where both sewage and rainwater enters the same system. These combined sewers include storm overflows that operate during heavy rainfall to prevent sewage flooding into homes and streets. Water companies are working to significantly reduce the number of times storm overflows operate, and nature-based solution such as reedbeds can help reduce the levels of contaminants in stormwater by acting as a filter. They also provide wildlife habitats and, compared with more ’traditional’ treatment methods, they have a lower carbon impact.

Alternative route for fish to swim upriver

Providing fish and eel passage around barriers in rivers such as dams can avoid blocking fish and eel movement which impacts their spawning, leading to declines in their numbers and harm to wider river ecosystems. Fish and eel passes enable easier movement upstream to spawning grounds.

Wetlands

Wetlands can help protect us from extreme weather events by storing rain like a sponge, which reduces flooding but can also help lessen drought by slowly releasing water back into rivers, lakes and groundwater. They can also reduce air temperatures and help to control erosion. They play an important role in improving water quality, are a crucial habitat for many species and provide opportunities for recreation and connection to nature. Wetlands can be reintroduced into more naturalised floodplains or included in new developments as a form of sustainable drainage.

Natural woodlands and hedgerows

Woodlands and hedgerows are an important part of our landscape and an integral part of our natural environment. Woodlands can sustain an immense range of wildlife, support human health and wellbeing, improve air quality, offer shade for crops and livestock, prevent nutrient loss and soil erosion, improve water quality and reduce flood risks.

Hedgerows support a rich variety of species and act as a link between habitats. They reduce the amount of fertiliser, pesticides and sediment that reaches watercourse by acting as a buffer, increase infiltration to the soil, and recycle nutrients.

Expanding or creating new woodlands and hedgerows to link them up is an important step towards recovering species populations.

Well maintained/tidy farm

Agricultural activities are one of the largest sources of pollutants to rivers, lakes and estuaries according to the Environment Agency. Adopting a range of pollution reduction measures across farms and rural industry to reduce soil erosion, pollution from nutrients, chemicals and fuels, will help to protect and improve our rivers and groundwaters.

Buffer strips along river bank

Buffer strips provide river bank protection to reduce levels of erosion and prevent agricultural/animal contaminants running into the watercourse, improving water quality. There is also the potential to encourage wild riverbank plants to flourish between the fence and river, increasing biodiversity and providing further resilience and bank protection.

Bathing water

Rivers and lakes are increasingly used for recreation, with associated health benefits and a more direct connection to nature. Water quality is important to reduce the risk of harm to recreational users and is influenced by factors including water company discharges, agricultural practices, septic tanks, pathogens from wildlife and road drainage. Real-time monitoring of water quality allows recreational users to make informed choices about the safety of their activity while improvements to water company systems and reductions in pollution from agriculture and urban area will improve overall water quality.

Managed livestock

Fencing and buffer strips provide river bank protection to reduce levels of erosion and prevent agricultural/animal contaminants running into the watercourse, improving water quality.

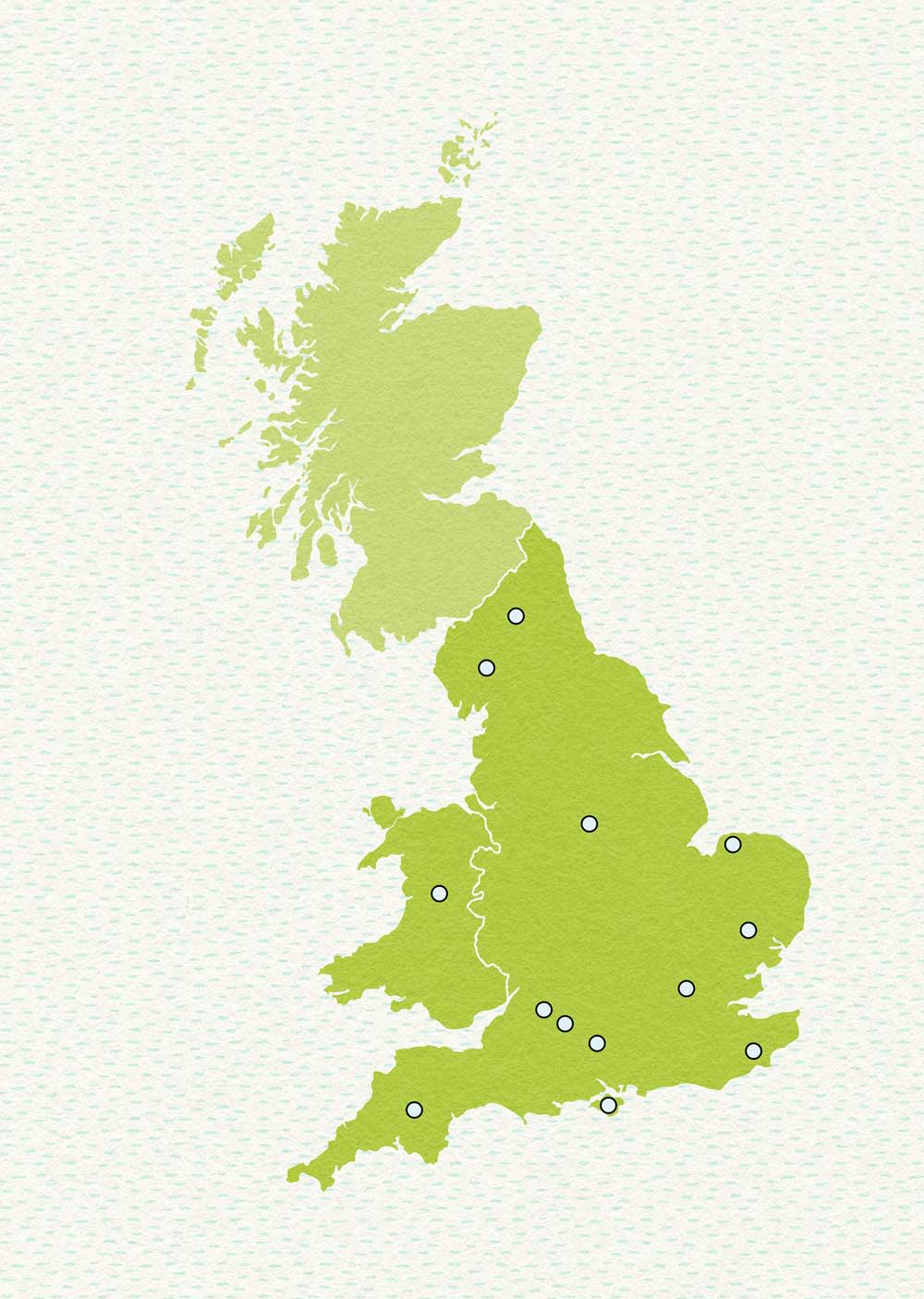

Case studies

Across England and Wales there are already many examples of partnerships working together to take a catchment approach to protecting nature and our watercourses.

Organisations mentioned in the following case studies who are not signed up members of the SSWAN Advisory Panel may not endorse the SSWAN proposals.

Water treatment wetlands, Ingoldisthorpe

Norfolk Rivers Trust in partnership with Anglian Water

Improving habitats and resilience, River Wylye

Wiltshire Wildlife Trust in partnership

with Wessex Water

Smarter water catchments, Thames river basin

Thames Water in partnership with Greater London Authority (GLA) and Waltham Forest Borough

Reviving rivers in England

Rivers Trust in partnership with Coca Cola

Addressing pharmaceutical effects on water quality, Cam and Wellow

Bristol Avon Catchment Partnership

Improving water quality and biodiversity

Eden Rivers Trust in partnership with United Utilities

Peatland restoration, Lake Vyrnwy

RSPB in partnership with Hafren Dyfrdwy (HD), the Welsh subsidiary of Severn Trent

Nature restoration, Haweswater

RSPB in partnership with United Utilities and farmers

Nature-based solutions for flood alleviation, Mansfield

Severn Trent Water in partnership with Mansfield District Council and Nottinghamshire County Council

Nature-based solution to flooding alleviation, Hanging Langford

Wessex Water in partnership with Wiltshire Wildlife Trust

Upstream thinking, Exmoor and Dartmoor

Dartmoor National Park, Devon Wildlife Trust, West Country Rivers Trust, Natural England, FWAG South West, National Trust, SW Lakes Trust, Cornwall Wildlife Trust, NFU, English Heritage, Environment Agency, and Exmoor National Park in partnership with South West Water

The Rivers Trust

Water for Tomorrow participatory model

Reducing the use of storm overflows, Hampshire and isle of Wight

Southern Water in partnership with the EA and parish councils

About us

SSWAN is a partnership of organisations who share the same goal: to find sustainable solutions for water and nature. We have drawn up proposals for regulatory reform of the water industry, based on a catchment-wide approach focusing on nature-based and low carbon solutions.

We all seek to restore and protect nature and to find sustainable solutions to ensure our waterways continue to sustain the health and wellbeing of people, as well as the natural habitats we all value and enjoy.

This alternative approach to managing and protecting the natural environment put forward by SSWAN sets out what is and isn’t working, what can be improved and what needs to be fixed. The proposals contained in this document are the result of months of discussions and roundtables.

The SSWAN proposals are not the final answer but are intended to act as a catalyst for further discussion to find a new way of working – putting nature first.

For more information, read the SSWAN Discussion Paper.

SSWAN Advisory Panel:

Alastair Chisholm, CIWEM; Shaun Spiers (Chair), Green Alliance; Nik Perepelov, RSPB; Martin Hurst, Sustainability First; Mark Lloyd, The Rivers Trust; Ali Morse, The Wildlife Trusts; Guy Thompson and Matt Greenfield, Wessex Water; Joanna Lewis, Wiltshire Wildlife Trust.

We are grateful to the following people who have been critical friends and offered their support, advice and guidance: Bart Schoonbaert (Arup); Mark Caines, Craig Lonie, Rohan Sakhrani and Sarah Latham (Flint Global); Gary Mantle; Heather Marshall (Mott Macdonalds); James Wallace (River Action); Lizzy Roberts, Costanza Poggi, Ellen Bassam and Katie Davies (Seahorse Environmental); Stuart Colville (Water UK); Charlotte Hanna (Wessex Water).

Let us know what you think or ask a question?

Latest news

Go With the Flow: Working with Nature and Managing Catchments

Speech was delivered by Ruth Kelly, Water UK Chair, at the City Water debate on March 21 2024

A water industry shake up could be a blueprint for the wider economy

This post is by Guy Thompson, group sustainability director at Wessex Water and managing director of EnTrade, a not-for-profit Wessex Water business.

Industry and environment groups come together to call for transformation of the water system

Organisations including RSPB, the Wildlife Trusts and Wessex Water have launched SSWAN, an advocacy group with the shared aim of delivering 'Sustainable Solutions for Water and Nature’.